Workshop XXXI, Bob Johnson, 18 January 2023

Bob Johnson, Department Chair of the Social and Psychological Sciences at National University in San Diego,

delivered a talk entitled The Titanic and the Stokehold: The Social History of a Chunk of Coal.

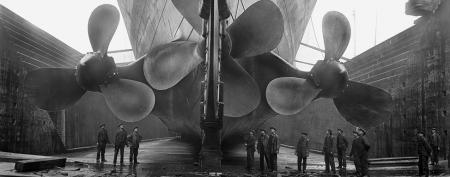

In this workshop, Johnson introduced participants to a new way of doing archival work focused on the material culture of fossil fuels by, in this case, pursuing the social history of a piece of coal from the Titanic that he bought on EBay. Johnson followed this chunk of coal from the moment it was extracted in the sooty coal mines of South Wales to the loading docks in Southampton, England, and then through its shovelling into one of the 159 coal ovens in the stokehold of the Titanic where it propelled a geography of consumption for the world’s bourgeoisie, its elite, and even its third class. Johnson’s approach here is to say that the Titanic, this monument to fossil capitalism, might be used as a metaphor for the ongoing stratification of class pleasures and pains associated with fossil capitalism, where some people are granted the right to thrive and survive the sinking of the metaphorical ship and others not.

To properly understand fossil capitalism, Johnson shows it necessary to juxtapose the geographies of extraction, where coal and oil workers are often immiserated and mutilated, beside the geographies of consumption where a dirty fuel like coal gets transmuted for the privileged classes into the pleasures of heated swimming pools, electric baths, incandescent lighting, and sweatless travel.

The connection between enrichment and exploitation, Johnson argues, became especially visible when the Titanic, this massive project run by a holding company owned by the banker JP Morgan, almost failed to launch in 1912 due to a month-long national coal strike over wages shutting down the coal flow. Morgan cannibalized other ships (coal from Appalachia, South Wales, Newcastle, the Scottish Black Country or elsewhere) to make sure his pet project launched successfully on time, and although Johnson is not quite sure where this piece of coal came from, he tells us that it was destined to be used on this transatlantic ship to propel capital’s project forward.

That project included transmuting black coal into clean electricity through 200 miles of hidden wires behind the walls of the Titanic where it performed delicate tasks like mood lighting, heating, ventilation, refrigeration, and cooking. This electric infrastructure gave the Titanic that high-class ambience that was sold to the privileged who enjoyed it while eating, drinking, conversing, and making love at sea at 23 knots an hour without any sweat on their part. Due to the ship’s intentional design, the Titanic’s paying passengers – like today’s consumers – were unaware of this chunk of coal. While first-class passengers took electric baths in the ship’s spas upstairs, only 5 to 10 feet below them the coal used to generate that electricity was sinking into the capillaries, the pores of necks, faces and hands of the Black Gang, working-class stokers, located out of sight in the boiler rooms and travelling like this chunk of coal in a closed circuit never to be visible.

Johnson concluded his presentation with the remarks that nowadays, the supply of coal and oil has specific purposes in the world, and we often forget about the products we are surrounded by. Cement, steel and glass are some of the dirtiest industrial products, as coal or oil is used to produce these. It is a fossil-centred system we are deeply embedded and surrounded in, and still, we do not initially think of coal or oil while encountering these products. In other words, our understanding of nature is shaped by an infrastructure of coal and oil directly contributing to climate change and, thus, a collapse of society, which is why we need to imagine an existence outside those fossil-centred systems.

Coal I Titanic I Fossil Capitalism I Workers I Social History I Bourgeoisie