Workshop XXXII, Matthew T Huber, 22 March 2023

Matthew T. Huber (Department of Geography and Environment, Syracuse University), author of Lifeblood (2013) and Climate Change as Class War (2022), reviews ecological Marxism in his presentation, “A Theory of proletarian ecology: limits and possibilities”.

Huber begins by asserting that we are losing the struggle over climate change, which is a struggle over power, and makes a call for the climate movement to build the power necessary to confront the fossil fuel industry and stop climate change.

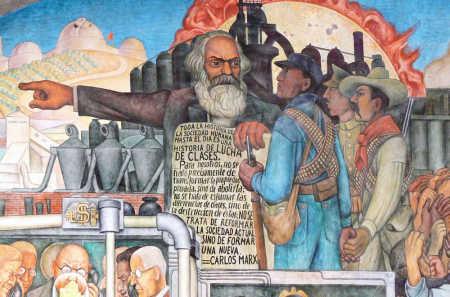

Ecological Marxism emerged in the 1970s out of the recognition that the working class was no longer an agent of revolutionary transformation as it used to be and that a new kind of politics – capable of acknowledging the ecological crisis caused by capitalism – was needed. Ecological Marxism departs from the working-class labour movement, which was seen as undermined by racism, sexism and hierarchical problems, to embrace a new coalitional and pluralist approach, also called a movement of movements. Huber distinguishes a type of ecological Marxism, which is strategically grounded on politics (advocated by thinkers like André Gorz, Raymond Williams and James O’Connor) from a sort that is theoretical and therefore less politically grounded (John Bellamy Foster, Kohei Saito, Jason W. Moore and Paul Burkett are examples).

It has been 50 years since the movement of movements came along and we are still not winning, Huber asserts, inviting us to reassess the strategic orientation of ecological Marxism. He calls for a reboot of ecological Marxism so that it keeps the centrality of working-class agency and thinks about the labour movement ecologically.

Ecological Marxism regards Marx’s definition of the working class as deeply ecological. The working class, according to Marx, is created when masses of people are violently separated from the land and thus the means of production. People in this context can no longer survive through nature and must survive through the market instead, accessing money and commodities. Money mediates our survival under capitalism, blinding us to the planetary destruction which happens behind commodities. Huber encourages us to reflect about the importance of working-class power, a key issue to address the ecological crisis, which must be thought of in terms of a global struggle.

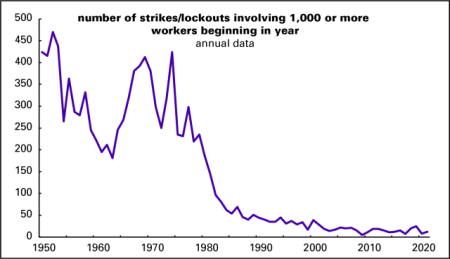

Why did Marx think that the working class has a unique power within the capitalist system which no other group in society has? The working class has strategic power because they do the work and they can also go on strike, forcing elites to respond to their unique power. The working class has this power, but they need to learn how to exercise it. Ecological Marxism must take power seriously, especially proletarian agency, which is necessary for the abolition of capitalism itself, a process that will involve restructuring production systems on a global scale.

Huber argues that the 19th-century revolutionary energy that Eric Hobsbawm discusses in The Age of Revolution: 1789-1848 (1962), which emanates from impoverished people recently disposed of their lands and forced to move to the city to survive via the market, extends till today (the Arab Spring being a case in point). The New Deal, which emerged during the first half of the 20th century to save capitalism from instability, dispersed and isolated workers (while it did not allow them to contest the production system), proving to be an energy intensive form of social reproduction.

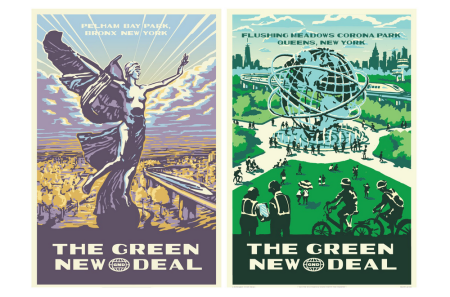

After the 1970s, the working class stopped using its power and became neutralised as people engage in what Michael Foucault calls ‘entrepreneurial life’; while in the post-1980 neoliberal period, we see the return of proletarian insecurity. Nowadays, as the Green New Deal (with its programme to solve climate change and rampant inequality) fails politically, Huber invites us to revive a broad working-class climate programme, paying special attention to the role that unions play in achieving large-scale policies. Decarbonisation will need the construction of new infrastructure and therefore a lot of industrial workers.

Huber claims that now that we have destabilised global geochemical cycles, it is urgent to take social control over production and deal with our global species-wide crisis. He reminds us that the politics about uniting humanity stated in ‘The Internationale’ could not be more relevant today.

Ecological Marxism I Proletarian ecology I Fossil fuel industry I Capitalism I Climate change I Working class I Strike I Power I Social reproduction I Green New Deal